In the early 1950s, Reiko Umetani Weston, a Japanese immigrant, moved to Minnesota, setting the course for the state to be introduced to Japanese cuisine — from teppanyaki to sushi — and for the city of Minneapolis to revitalize its riverfront, too.

Weston was born in Japan in 1928, the daughter of an admiral in the Japanese navy. After World War II, she worked as a secretary in Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Tokyo office, where she met Army Air Corps pilot Norman Weston, a native of Minnesota.

In 1953, the couple, as well as Reiko’s parents, moved to Minnesota.

Searching for something for her parents to do in Minnesota while she attended classes at the University of Minnesota, Weston opened the state’s first Japanese restaurant in downtown Minneapolis in 1959. Her mother cooked, and her father greeted guests at the restaurant named Fuji-Ya, translating to “second to none.”

In that first year, Fuji-Ya grossed $50,000, quickly outgrowing its 25-seat restaurant space. So Weston left school and spent two years searching for a new location. In 1961, she found a site in the Minneapolis milling district in the burned-down remains of two flour mills on South First Street near Central Avenue and the Mississippi riverfront.

Once home to booming sawmilling and flour industries, by the 1960s, the Mill District’s riverfront was in decline, becoming a collection of things that industry left behind — “abandoned foundations, burned-out building shells and contaminated soil,” wrote Kimmy Tanaka and Jonathan Moore in a Minnesota History magazine article, Fuji-Ya, Second to None: Reiko Weston’s Role in Reconnecting Minneapolis and the Mississippi River.

It was an unusual location choice.

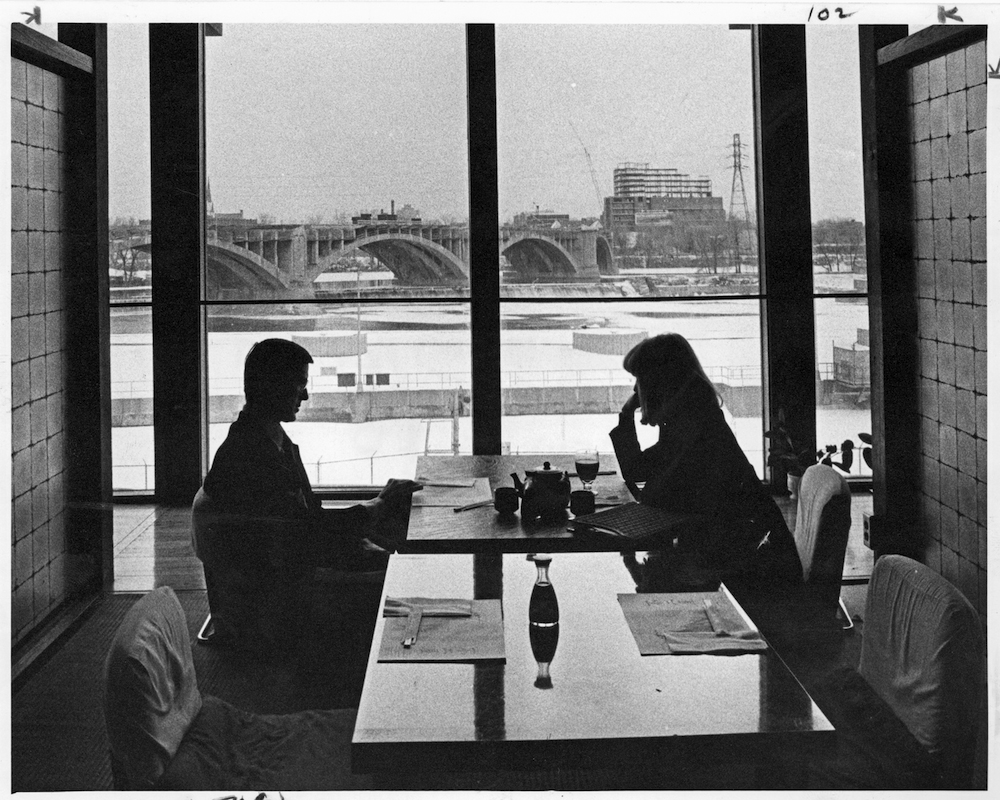

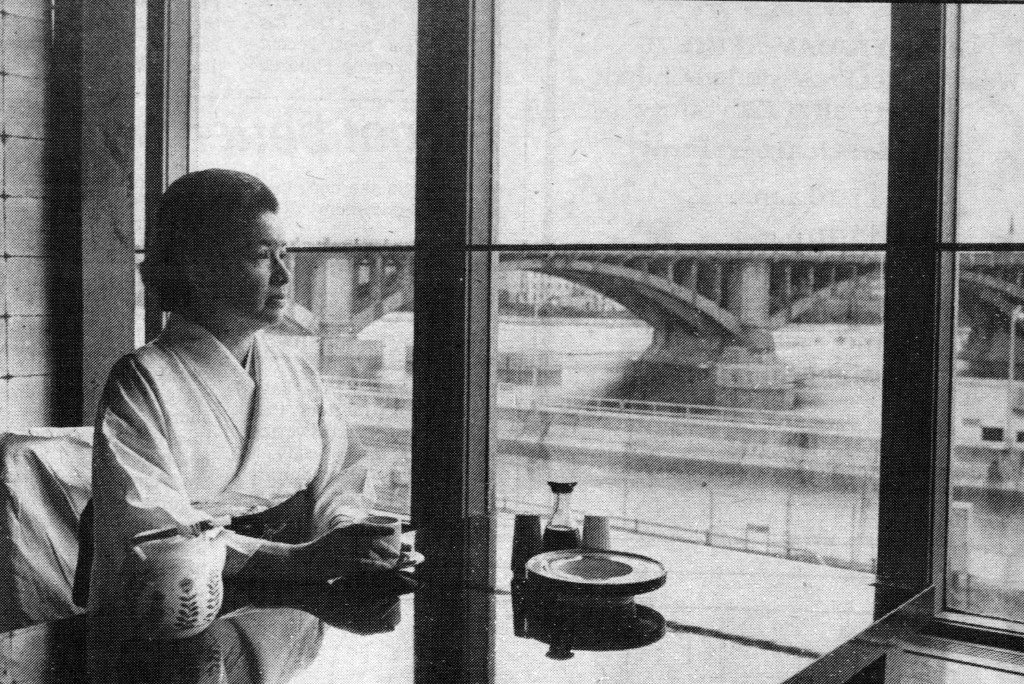

But Weston, who paid $20,000 for the site near St. Anthony Falls, said in a Minneapolis Star interview: “The Japanese love rivers and bridges and waterfalls. It’s the perfect setting for a Japanese teahouse.”

Opening in 1968, the new Fuji-Ya was built on top of the historic mill foundations and featured elements of a traditional Japanese home as well as a floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking the river. At first, the restaurant served primarily suki-yaki, a one-pot Japanese dish cooked tableside. But within a few years, Weston added a teppanyaki area with theatrical chefs, cooking and tossing knives in front of diners. In 1981, Fuji-Ya introduced the first sushi bar to Minnesota.

Soon Weston had amassed a Twin Cities restaurant empire with Fuji-Ya, the cafeteria-style Fuji International on the West Bank; Taiga, Minneapolis’ first dim sum restaurant at St. Anthony Main; and Fuji Express in the Minneapolis skyway. In 1978, the Star Tribune reported that her businesses had more than 100 employees and earned $3 million annually.

Weston was named Minnesota’s Small Businessperson of the Year by the U.S. Small Business Administration in 1979 — an honor that included an invite to the White House — and became the second woman added to the Minnesota Business Hall of Fame in 1980.

In the midst of all this, Weston suffered a stroke and her daughter. Carol Hanson, began helping out with restaurant operations. Even with her health issues, Weston still had grand visions for some of the undeveloped land she’d bought to open Fuji-Ya; she contacted an architect about designing a Japanese-style hotel and spa to join her restaurant on the riverfront.

Historical Society

But in 1987, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board (MPRB) acquired Weston’s land between the restaurant and the river (Fuji-Ya’s parking lot) through eminent domain to build West River Parkway. As Fuji-Ya litigated against the MRPB, arguing that the loss of the parking lot had hurt the restaurant’s business, Weston suffered a heart attack and died at age 59 in May 1988.

Hanson took over the business, and the lawsuit ultimately settled with the MPRB acquiring the Fuji-Ya property for $3.5 million. With its land now owned by the MRPB, Fuji-Ya closed its riverfront location in May 1990. In 1998, Hanson revived the Fuji-Ya name and opened a new Japanese restaurant on West Lake Street in Uptown.

In recent decades, many other businesses have followed Weston’s lead and relocated to the Mississippi riverfront, and the Minneapolis Mill District has been revitalized into a vibrant, booming neighborhood.

Meanwhile, the Fuji-Ya building sat empty and unused until fall 2017 when the MRPB razed the restaurant for a new park pavilion and restaurant, part of its forthcoming Water Works park development.

The MRPB will retain the original mill ruins that Fuji-Ya was built on, and architectural elements from the restaurant were salvaged to incorporate into Water Works.

Today it’s clear that Weston was years ahead of her time when she chose that blighted patch of riverfront for her new restaurant in the 1960s. As longtime local journalist Barbara Flanagan wrote in the Minneapolis Star in 1968: “Nobody looked twice at the riverbank site until Mrs. Weston got there. Leave it to a woman to show the way. Now everybody’s interested in the river.”

Lauren Peck is a public relations specialist for the Minnesota Historical Society.